|

What initiated this ongoing political war was a

petition submitted to the Massachusetts

Legislature from the West Village of Longmeadow

asking the Commonwealth to separate the West

from the East Village and to create two

independent towns out of the original

Longmeadow, which had been set off from

Springfield in 1783. The petitioners cited

complete "diversity of interests" and lack of

communication between the two very distinct

villages. Even

geography played a role. A member of the

Massachusetts House referred to the territory

between the villages, as "a howling wilderness,

and one might believe that a crow going across

would be obliged to carry his rations with him."

Centennial 1883

Yet just a few years earlier, in 1883, about

2,500 people had gathered on the Green, under a

huge tent in the West Village, to celebrate the

town's Centennial. The Springfield Republican of

October 18 described Longmeadow's celebration as

"one of the rare occasions whose excellences far

surpass their prefatory promise; for nothing of

the sort was ever more modestly heralded, and

assuredly nothing of the sort was more rich,

satisfying, and complete". Various newspaper

reports indicated people from all over the lower

valley had come to the town on the 17th, with

tethered horses and other conveyances parked up

and down the street for miles. The East Village

had a large number present, and there was no

outward indication of any tension between the

two villages.

Emerging Differences

But in the years after the Civil War,

pre-existing

differences began to

become stronger and rise to the surface. These

differences involved population, ethnicity,

economics, spatial characteristics, and a

changing view by the leaders of the nature and

basic character of each village. At the bottom

of all the differences was a natural resource:

brown and red sandstone, which was present in

the East, but not the West.

While not as volatile as oil or as

valuable as gold, this stone was somewhat rare,

and it had become a very important building

material. During the l9th century there was an

increased demand for building material in a

growing American economy. Coupled with expanding

and more advanced mining operations, the East

Village experienced a continually expanding

economy. Longmeadow brown sandstone, and

particularly red sandstone, became famous for

its use in a variety of places, such as Yale,

Princeton, Wesleyan, the Smithsonian in

Washington, and Trinity Church in NYC, to name

just a few.

Population

The rise of this stone mining activity led to

some significant population differences. The

variety of task associated with the mining, such

as cutters, polishing teamsters, stables,

harriers, and boarding house owners led to an

influx of Canadians (from Nova Scotia and New

Brunswick), followed by Poles, Swedes, and

Italians. One social consequence was the rise of

religious and social organizations to meet the

needs of this growing multiethnic population.

The overall growth of population and industry

put pressure on the entire town to increase and

improve the physical infrastructure. This would

become one of the issues to surface in the 1880s

and exacerbate other differences.

The growing population of the East was in

contrast to a level and then declining

population in the West. This was

in part due to the

earlier settlement (by over a century) of the

West and the inability of agriculture to

continue to support large families. By the early

1800s many of the sons of "Street" families

(especially the Coltons) had gone into religious

training for missionary work and /or career

advancement or had moved to the growing American

western frontier

(leaving behind an imbalanced population: more

females to males). This situation set up the

long-term decline in population by lowering the

overall birth rate of the West Village. While

new families moved in, they tended to be past

childbearing age; they were the initial

beginning of Longmeadow becoming a retirement

village, or a refuge from the world for

wealthier individuals. This "new" population

would be less supportive of increasing taxes for

infrastructure development of the East Village.

At the same time, some of the older farm

families were experiencing declining revenues

from their aging farms.

The East Village

Differences by themselves don't automatically

mean

conflict. People from

Longmeadow Street in the West and from other

locations had been moving a few miles

eastward ever since around 1740. They did not

emulate the linear structure of the West (the

"Street"), but had scattered

farm lots and houses.

By 1829 there were enough families in the

eastern part to form their own church, and the

nucleus of the East Village now existed. But the

population of both villages was still basically

of the original Puritan stock that settled the

lower valley two centuries earlier; both

villages were still basically white,

Anglo-Saxon, Protestant communities. But here

was one subtle but vital difference evolving.

The East had a younger population, and

it was the "frontier"

for regional immigration, while the West's

population was gradually aging.

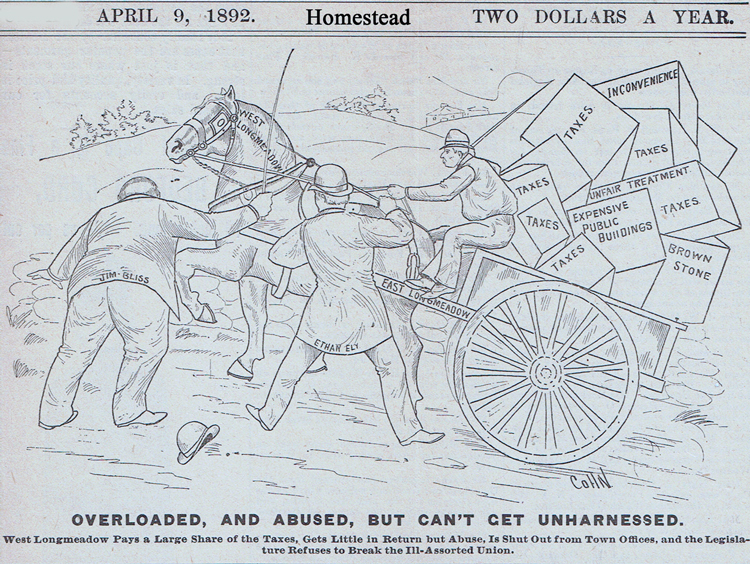

[click image to enlarge]

Organizing for Division

Beginning in the Civil War era, there were

occasional discussions and rumblings from one

village or another about separation. But it was

in 1891 that the first full-blown move for a

division of the town occurred, and it came from

the West Village. A letter dated December 7,

1891 was circulated, asking for opinions and

support for "a division of the town... with a

view of submitting the matter to the

Legislature...". The letter cited reasons that

have been referred to here; but an important

additional reason referred to the "many

improvements needed by the West village..." that

the people of the other village didn't care

about. This list was the basis for all future

discussions and of the formal petition submitted

to the Legislature on December 7, 1892 (exactly

one year later).

Political War

Town meetings over the next three years became

more

noisy and less civil.

Each side accused the other of a variety of

Machiavellian moves, illegal activities, and

lack of impartiality by the Moderator (elected

from the East by the 2-to-1 voting advantage of

the East Village).

The

Springfield papers, of course had a field day

with this situation. "FEUD RENEWED," "ANNUAL

FRACAS," and "STORMY MEET|NG" were banner

headlines in the local papers.

One

veteran Selectman from the West, Charles Newell,

was arrested at one meeting. He was vigorously

and loudly protesting and accusing the Moderator

of cheating by not allowing a ballot on the

question to include an option for a pro-division

vote.

Legislative Intervention

Meanwhile the legislature had been considering

the question of division for several years. The

first YES vote for division in early 1893 was

vetoed by Gov. William Russell.

One reason was that

the tax burden of each village would change

significantly: the West would decline and the

East increase. Also, a division would create a

town (the West village) that would have a

population of only 570 and a little over 100

voters. Another reason was that on two separate

occasions there had been an emphatic 2-to-1 vote

against division, and the governor saw no real

grievance that should override the explicit will

of the majority to keep the town whole. However,

another petition to the Legislature in early

1894 received a positive vote and the signature

of Gov. Greenhalge.

At the

time it was speculated that the high-handed and

arbitrary tactics of the East village and its

leaders convinced the new Governor that the

growing "war of the communities" could only end

by creating two separate towns.

So on July 1,

1894, the "new" Town of Longmeadow was born.

When the new town received the news of the

coming split on May 22, "bells were set ringing

merrily in Old

Longmeadow Street... bonfires were lighted and

firearms blazed. The village band paraded the

streets reinforced by horns and shouts... and

firework....".

Leadership and a Vision

Was this division inevitable? What role did

individuals play in these events? And perhaps

most important, what values informed the actions

of the leaders and their vision of an

ideal community?

A

preliminary answer is suggested here. Certain

names show up in the drive for division and the

establishment of a new town government and the

necessary infrastructure, like a water supply

system (beyond personal wells, brooks, and water

troughs on the "Street") Some of these people

controlled large tracts of land, some that were

estates of some of the older farmers; some got

involved in real estate developments like South

Park Terrace, or were shareholders in the new

electric trolley lines. The new town with its

historic linear development and open land to the

east of the Street was a resource perfect for

the building of a suburb for the burgeoning city

of Springfield. The Springfield Republican had

hinted at this in a February 1892 editorial

arguing for the division of the town: lt noted

the East's future prosperity would grow with the

quarries, and the West's "nearness to

Springfield" will take care of the West Village.

And finally, what of the vision of

the

West's leaders? They

were inheritors of and

still strong believers in the old Puritan vision

of a "City Upon a Hill" articulated by the

Puritan leader John Winthrop in 1630 with the

founding of the Mass Bay Colony. The belief in a

superior people and culture that was inherent in

Puritanism still existed in the late 1800s.

It had

morphed into a set of beliefs that fall under

the label of Social Darwinism. People of

Anglo-Saxon heritage were believed to be at the

top of the population pyramid, in contrast to

the "New Immigration" from southern and eastern

Europe. The Chair of the Longmeadow Centennial

"welcomed on behalf of Mother Longmeadow all her

Saxon children" (but made no ethnic reference to

other groups of people residing in the East

Village). The keynote speaker, in lecturing on

Longmeadow's early history referred to inferior

and savage Indians, and French colonists

(particularly nuns and priests) in derogatory

terms. Another speaker referred to the Old

village as a "select and favored refuge..."

where there was "no air of foreignness as you

would find in the coastal cities." He told his

audience that the beauty of the old village was

that the "original blood" of the Puritan

middle-class English migrants has continued

"without any general admixture of foreign

elements."

It

was in this cultural context that began the

discussions on

the "Street" that

would lead to a movement for separation from the

East Village. There were all the other

differences,

from stone to squabbles to suburb, but the

identification of the West Village as a "happy

harbor of God's saints" certainly provided a

rationale for creation of a "new" Longmeadow

over the next generation. The first major

planned development was called South Park

Terrace, (south of the Forest Park boundary and

fronting the "Old Longmeadow Street").

Its

advertising booklet referred to the peace and

quiet and tastefulness and temperate enterprise

and quick trolley ride

to downtown Springfield owners.

|